"Religious Naturalism: A Theology for UU Humanists" by Demian Wheeler

Part II

In the early nineteenth century, the Unitarians were the leading representatives of American theological liberalism. They still are. I think it is fair to say that Unitarian Universalism is the foremost liberal religion in America today. And, to me, religious naturalism is the quintessential expression of a liberal theological outlook. Like UU liberals, religious naturalists are anti-authoritarian to the core, insisting on a free and responsible search for truth and meaning. Like UU liberals, religious naturalists draw on a diverse array of sources such as science, poetry, art, and the world religions. Like UU liberals, religious naturalists look to the guidance of reason and experience, including the “direct experience of that transcending mystery, affirmed in all cultures, which moves us to a renewal of the spirit and an openness to the forces which create and uphold life.” For the religious naturalist, that transcending mystery is nature itself.

Religious naturalists and Unitarian Universalists are also fellow travelers on liberal theology’s middle path. Think about what religious naturalism is. First and foremost, it is a form of naturalism. For the religious naturalist, nature is ultimate; there is nothing above, beyond, or in addition to nature. For that reason, the religious naturalist is vehemently anti-supernaturalistic. There are no supernatural entities of any sort, no heavenly realms or otherworldly destinies, no overarching cosmic purpose or direction, no miracles or special revelations, and no immortal souls that live on after death. Such items, as Wesley Wildman cleverly puts it, are not on the religious naturalist’s “ontological inventory” (Wildman 2014: 42-43). Nor is there any anthropomorphic divine being determining or guiding the course of history. Once again, what there is, and all there is, is nature. This means that there is nothing outside of nature, and anything that does exist, including humans and their civilizations, is a part of nature.

All that being said, religious naturalists are not “slash-and-burn” atheists, to use Chet Raymo’s hilarious label (Raymo 2008: 102)! Rather, they are liberals, attempting to forge a middle way between superstitious religion and evangelical atheism. Religious naturalists are atheistic when it comes to a personal God and all the other supernatural trappings. But they still want the bath water, to draw on Raymo again—i.e. a sense of reverence in face of the wonder and mystery of nature. Critics frequently dismiss religious naturalism as oxymoronic, assuming that religion is inherently supernaturalistic, and naturalism inherently anti-religious. However, religious naturalists challenge these widespread assumptions, affirming the promise of a nonsupernaturalistic religiosity, of a religion-friendly naturalism. In other words, for the religious naturalist, supernaturalism and secularism are not the only options; there is a third possibility, a middle road that might be described as “spiritual but not supernatural.”

Lest you be scared off by the word, “spiritual” is derived from the Latin verb “to breathe.” Perhaps, then, “spirituality” simply has to do with contemplating and paying attention to that which is breathtaking. In that sense, science can actually be “a profound source of spirituality” inasmuch as it reveals just how breathtaking reality is. To quote Carl Sagan again: “When we recognize our place in an immensity of light-years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual” (Sagan 1996: 29). So, one does not need to be a supernaturalist to have spirituality. As the religious naturalist Jerome Stone declares, we can have “naturalized spirituality.” We can be “open to the treasures of this world, to its joys and even its heartaches,” without trying to escape to “a higher realm” (Stone 2017: 76).

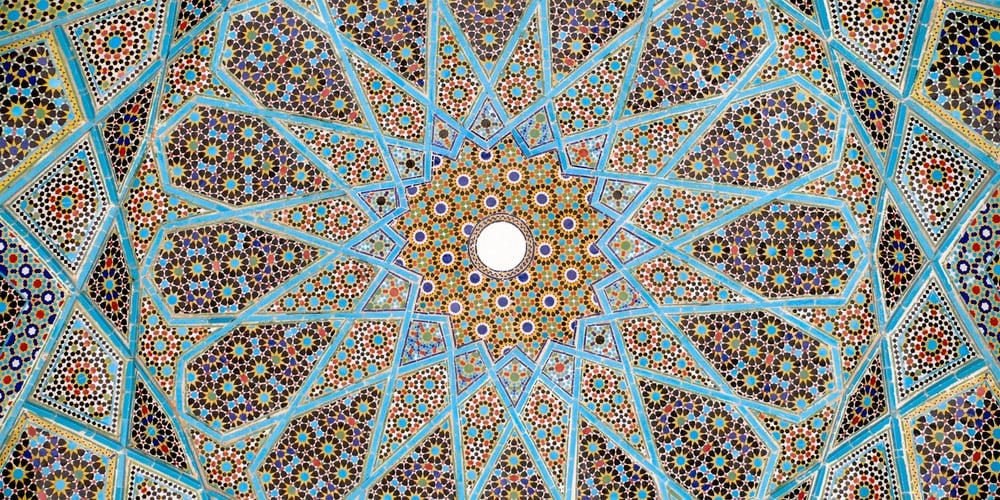

Now, this does not mean that religious naturalists make different claims than other naturalists. Again, a religious naturalist is just as doggedly naturalistic as a non-religious naturalist. What distinguishes the religious naturalist is not so much a set of beliefs as it is a suite of attitudes and affections. As Loyal Rue clarifies, a religious naturalist is someone who “takes nature to heart,” someone who experiences and treats nature as sacred—i.e. as ultimately important, worthy of reverence, and beyond our control (see Rue 2011). The sacredness of nature lies in its depth dimension, to borrow a concept from Paul Tillich. “Depth dimension” is shorthand for nature in all its transcendent splendor and terrifying ambiguity, its incomprehensible vastness and microscopic complexity. It refers, for example, to the intricateness, beauty, and value of every detail of creation—a swirling galaxy, a DNA double helix, a Bach cantata; to the marvel of consciousness and the staggering improbability of its emergence; to the infinite processes that create, sustain, and eventually destroy all that is; to the sheer mystery of why there is anything at all rather than nothing.

In short, nature is enough; it is deep, sublime, powerful, vast, awesome, and mysterious enough to elicit our fidelity and religious commitment, to arouse profound spiritual feelings of wonder and thanksgiving, awe and humility. We do not need to place our faith in otherworldly gods, nor do we need to long for another life in another realm beyond nature, because this world and this life can provide ample context and support for finding purpose, value, and meaning.

That’s religious naturalism in a nutshell. And religious naturalism happens to be undergoing a revival of sorts. The scholarly and popular literature on religious naturalism has increased substantially over the last twenty years. There are a handful of organizations and websites devoted to the promotion of religious naturalism. And more and more people today, especially among Gen Xers and millennials, are finding religious naturalism to be an attractive option.

Why?

Well, I have already talked at length about the religious promise of religious naturalism. Religious naturalism enables one to live a religious life as a naturalist, to have a robust spirituality without invoking a supernatural God or supernatural phenomena of any kind.

There are all sorts of other advantages to being a religious naturalist. To begin with, nature-centered spiritualties, like religious naturalism, enjoy a heightened ethical urgency and relevance in an ecologically imperiled era such as ours. To be sure, no spiritual orientation, including religious naturalism, will solve our environmental problems—e.g. global climate change. However, as Jerome Stone points out, upholding the sacredness of the whole interconnected web of being—not only human existence, but also nonhuman lives and habitats and even far-flung stars and galaxies—will have a pragmatic effect on our attitudes and actions (Stone 2017: xviii).

Religious naturalism also eliminates the need to brood over theodicy. Instead of trying to figure out why an all-good and all-powerful God would create a world filled with so much evil, misery, and death, religious naturalists, as Donald Crosby contends, assume a posture of realism and acceptance with respect to the ambiguities of life—“no pap, no panaceas, no empty promises” (Crosby 2008: 108).

Finally, religious naturalism overcomes the age-old conflict between religion and science—and not by cherry-picking the sciences in order to confirm our religious presuppositions. On the contrary, religious naturalists are interested in developing spiritual, ethical, and theological responses to the scientific worldview currently on offer—even if it challenges and alters our religious assumptions. For example, rather than attempting to reconcile evolutionary science with the premodern and inescapably anthropocentric creation myths in the book of Genesis, religious naturalism adopts the “epic of evolution” as its sacred narrative. Be that as it may, as much as religious naturalists privilege science and the scientific method of knowing, they are opposed to scientism, the presumption that the sciences have a monopoly on truth. Maybe philosophy, music, and even religion reveal things about nature that astrophysics and biology do not. And, as much as scientists have discovered about the natural world, nature always remains largely hidden behind a dark veil, behind a cloud of unknowing. Thus, the religious naturalist is part stubborn rationalist and part apophatic mystic, someone who embraces the facts but also honors the mystery. The religious naturalist responds religiously to the world as we empirically find it yet stands in silence and holy fear before the inexhaustible depths of nature.

This is Part II of III from Demian Wheeler: "Religious Naturalism: A Theology for UU Humanists"

You can read Part I here.

Demian Wheeler is Assistant Professor of Philosophical Theology and Religious Studies at United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities. He came to United in 2015 as a Louisville Institute Postdoctoral Fellow. He received his Ph.D. from Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York, where he specialized in American liberal theology. His research and scholarship focus on the early “Chicago school” of theology and the streams of theological and philosophical thought that have flowed into and out of it—e.g. pragmatism, historicism, empiricism, and religious naturalism. Wheeler has published a number of journal articles and scholarly essays on empirical theology, religious (and ecstatic) naturalism, and process philosophy, among other topics. He is also the co-editor of Conceiving an Alternative: Philosophical Resources for an Ecological Civilization (forthcoming with Process Century Press). His first book, Religion within the Limits of History Alone: Pragmatic Historicism and the Future of Theology, is currently being reviewed by a major university press. Wheeler lives in Minnesota with his wife, Victoria, and their son, Shailer. He is a Unitarian Universalist.

Your Comments :