Back when I was a CPE educator in a large, metropolitan hospital system, I often gave my students an interactive assignment for their first day of training. I asked them to place themselves in busy lobbies, cafeterias, and waiting rooms at their assigned hospital, then sit at a table with open faces, a video camera, and a sign that said, “Tell Me What a Chaplain Does?”

Back when I was a CPE educator in a large, metropolitan hospital system, I often gave my students an interactive assignment for their first day of training. I asked them to place themselves in busy lobbies, cafeterias, and waiting rooms at their assigned hospital, then sit at a table with open faces, a video camera, and a sign that said, “Tell Me What a Chaplain Does?”

They were to ask random hospital visitors, vendors, administrative staff, family members, Starbucks baristas, and anyone else passing by to provide a definition and describe the activity of a chaplain along with answering a few questions:

- What does a chaplain do?

- Where do they work?

- Have you ever met one?

- Why would you need one?

The responses fell cleanly into generational assumptions. Elders and Baby Boomers described chaplains as the people you call when someone is dying in the hospital, or they recalled a chaplain who served with them in the military. Some remembered a chaplain who visited a relative in prison and helped turn that person’s life around. Many younger adults had no idea what a chaplain did, and the remarks that accompanied their blank stares often led to laughter at the tables. For many of the interview subjects, the word “chaplain” evoked tropes and stereotypes, ranging from Father Mulcahy on the television show M.A.S.H. to childhood memories of a somber looking stranger showing up at the death of a loved one.

As they gathered the data from these exercises, my students saw clearly that less than 35 percent of those interviewed had any real clear idea of what a chaplain does.

So What Does A Chaplain Do?

Chaplains have always been ambiguous figures, ministers whose duties lie away from church authority or the demands of a congregation. Historically, chaplaincy has been associated with three institutions: prisons, hospitals, and the military. If you weren’t sick, in prison, or a soldier, you had little contact with a chaplain. And even if you were, you might never see one. In these secular institutions, the chaplain was the explicit broker of spiritual care in a regulated and rigid environment. Their work was specific to their particular denomination--Catholic priests would tend to Catholic patients, Methodist to Methodists, and so on.

Today, however, chaplaincy is far more generalized and less identified with any particular religious or spiritual tradition. While a person must be ordained through a denominational process in order to enter the chaplaincy certification process, the actual work of chaplaincy often has little to do with religion or spirituality at all. The most competent chaplains today are cognizant of the religious, social, cultural, political, and economic identities of care-seekers. In addition to their theological training, they have wide-ranging intellectual interests and are knowledgeable of current events, urban cultural norms, rural displacement, and what the CDC classifies as “deaths of despair”--suicide, overdoses, and alcohol-related illnesses.

Chaplains have a broad, intersectional understanding of cultural, religious, and spiritual syncretism and its many expressions. They have a deep well of curiosity, compassion, and critical analysis which is crucial for the current landscape of chaplaincy. Chaplains demonstrate and embody an authentic comfort, mingling with the wrinkles of humanity in a non-imposing, non-coercive, non-judgemental manner that lets care-seekers take the lead.

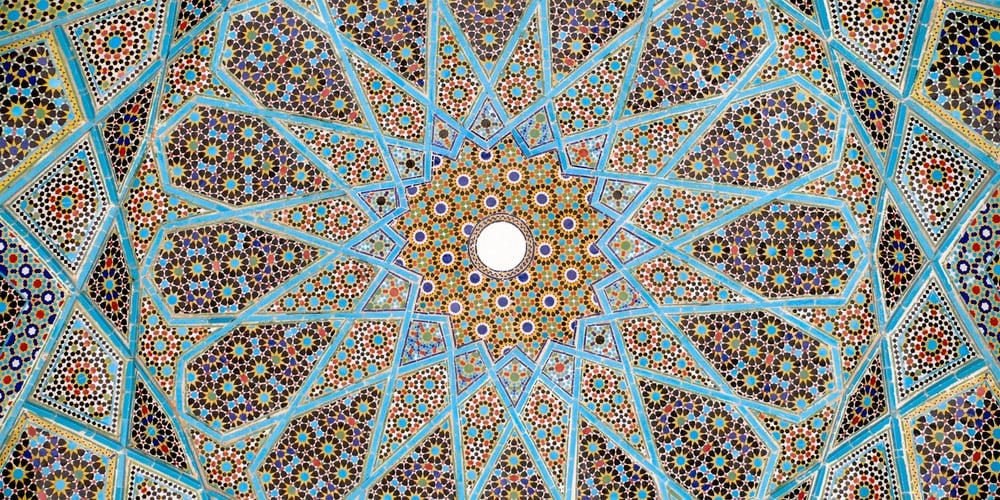

At its core, chaplaincy is about taking the sacred out of the church, mosque, synagogue, or temple, and bringing it to the people, wherever they are and whatever their circumstances. It means acknowledging the sacred in hip-hop, Burning Man, Beyonce’s Lemonade, and the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally. It means bringing curiosity, wonder, and awe to all interactions. Chaplains address particular needs and assist care-seekers in meaning-making and reflective processes during incarceration, on Navy ships, in treatment programs, on college campuses. In all these settings, chaplains provide the non-religious and the religious a rich tableau of authentic human caring. They do not bring sympathy or spotlight empathy. Instead chaplains bring a rational compassion to their work that honors the entry points and boundaries of caregiving.

The word chaplain comes from the Latin word for a cloak--its use for ministry grew out of the story of St. Martin meeting a man begging in the rain with no cloak. If St. Martin had met the man's need by giving him his own cloak he would have shifted the problem to himself, so instead, he tore his own cloak in two and shared it, half for the man and half for himself. It’s a fitting image: A chaplain shares support with those in the storms of life, working alongside those in need of help to offer spiritual care and direction in those difficult times.

A Broader Scope for Chaplaincy

As chaplaincy evolves to be less religious, more humanistic and broad-based, the profession has an opportunity to assist people as they search for meaning and purpose in new places. This creates space for those interested in chaplaincy to expand their ideas of what chaplaincy can look like.

Chaplains as spiritual curators: A strong faith community encourages its members to develop a robust theology/philosophy based on experience, reason, and spirit guided by a set of denominational creeds or expectations. Yet given the increasing religious ambiguity in our culture, it’s becoming more common for people to shape their beliefs outside of an institutional community, practicing meaning making and spiritual exploration in ways that are more difficult to connect to a specific faith tradition. Because of their robust theological training, chaplains are in the unique position of being able to mine and dig into a person’s faith journey, whatever that may be, without being bound to institutional assumptions. As chaplains, we are free to journey with people as we address the particular needs of an individual’s narrative. We are able to draw on a wide variety of spiritual, religious, and philosophical content and resources to assist care-seekers as they affirm their current beliefs or explore new possibilities for comfort and community.

Chaplains as interpreters: Interreligious chaplains are well-versed in the variety of global spiritual texts, able to decode the languages of spiritual pain, crisis, and trauma for care-seekers. These texts include ancient sacred texts, but they can also include the mantra of positive thinking, the books of Joyce Myers, or the Pulitzer Prize-winning lyrics of Kendrick Lamar. Having studied world religions in seminary is not enough. Chaplains are ordained through denominational processes, but they deepen their knowledge through experience, visiting Hindu Temples and hanging out with a Hindu family during Holi, eating sweets and talking about baseball. They take time to learn precisely why Black folks are suspicious of the medical establishment and the legacy of the Tuskegee experiment. They build relationships and study history and unpack biases in order to recognise that a poor white man from Appalachia might not be able to read, but he can recite poetry flawlessly. Chaplains must always study the new “texts” that are shaping and forming the culture of care-seekers.

Chaplains as prophetic voices: Sometimes chaplains take on the role of the prophet, standing out in the face of injustice or unethical issues. This can manifest itself in the role of arbitrator between people at odds--patients and their doctors, workers and their supervisors, children and their parents. A chaplain being in the right place at the right time can help institutions avoid problems and public scandals and guide families safely through the kinds of ethical decisions that can too often break them apart. The specific training of chaplains makes them well-suited to mediate and intervene on issues of social justice, pluralism, and oppression.

As the religious landscape in the US shifts, there is a growing need for people who can navigate those shifts with wisdom, solid training, and comfort with a range of spiritual expressions. While many chaplains still choose to work in hospitals, prisons, and the military, there are increasingly chaplains in corporate settings and inside the justice system. There are chaplains working with college students and serving alongside social service providers. There is no end to the need for care, for comfort, for guidance, and chaplains stand ready to meet the need.

Considering a career in chaplaincy?

Your Comments :