Open my eyes, that I may behold

wondrous things out of your law (Ps. 119:18, NRSV).

We do not exist outside of our relationships. We become who we are only in relation: we are network creatures. (Catherine Keller, On the Mystery, 32).

At United, theology is often related to optics; we are asked, "What do you see?" This phrase might come up in a Bible class, where we examine a biblical passage and consider how we fit into the narrative and how it speaks to us. Or it might be in Religious and Theological Interpretation, when we explore what it means to see into a text and interpret it. In Theology and the Arts courses, we practice looking at images to find out what makes something explicitly or implicitly religious, what it means for a film or a painting or a piece of music to be meditative, constructive, even prophetic. And of course the work of propheticism, which is key to social transformation, has always been about recognizing what is broken in this world and visualizing a new, more just world.

What do you see?

With a history of commitment to LGBTQ people, United asks these theological questions alongside questions of sexuality, gender, and Pride. We are all invited to ask: What do I see in God, the world, in other people? How do the world, God, and other people see me?

At the end of this Pride month, it strikes me that Pride itself is also concerned with optical questions. Am I seen? In relation to whom am I being seen? Who am I seeing? Optics have come into even greater focus because of social distancing. A lot of us are celebrating Pride through online platforms: digital events, Facebook Live drag shows, community forums, or watching the documentary Disclosure on Netflix. Additionally, we embrace Pride amidst the movement for Black Lives; amidst attacks on LGBTQ healthcare; amidst violence against transgender women, particularly of color. In the middle of these challenges, we share and sculpt our images and identities on social media platforms. While all senses are engaged, sight dominates.

Flags, Visibility, and Identity

Some of the most striking visuals of Pride are the plethora of flags, a majority of which have been produced in the last ten to twenty years, long after the rainbow flag was introduced. This year, I have noticed how often the colors in the agender flag, in the trans flag, in bisexual flag, etc. refer either to an identity (androgynous, trans man, agender, trans woman, pansexual, etc.) or to the person at the end of attraction (same sex, different sex, multiple sexes, etc.). These flags represent coalitions of identities. On one hand, there is power in saying who we are and who we are with. On the other hand, I sometimes feel stuck, as though these flags are saying, “We exist,” without saying anything about our values or expressing our dreams for a more just world. The annoying “radical” voice in me questions if these flags are just an effort to grab a piece of the oppressive and dominant culture.

I don't mean to devalue identity completely. Identity is something queer people feel strongly about. It's what others use to define us. Sometimes identity is a political necessity: We need to be seen not as a fluctuating mass, but pinpointed as something solid and therefore “real.” But I also think identity is theological and ideological: something I am or have is shaped by certain Christian or Platonic ideas of the soul, the Enlightenment Mind, the Romantic Self, in and against the world. In these frameworks, the identity/self is true, eternal, and of greater importance than that which is changeable.

I fear the idol of stasis. Personally, I find a difficult contradiction to bear when my use of trans (the root being “across,” implying direction, action, change) turns into a static identity. I am worried how taxonomies of identity--veering strongly toward essentialism and fixed categories of the self--are antithetical to the movement “trans” implies. I am concerned that in our current culture, “to be something” is too often interpreted as “to be something at the expense of all other things.”

In a pluralistic seminary, we learn that oneness does not have to exclude many-ness, that unity is community, that the paradigm of claiming an identity at the exclusion of all others does not have to be true. Gilbert Baker’s rainbow flag does represent a certain community which can be taken as an identity, but the original 8 colors do not represent identity labels. Rather they represent values and themes: hot pink/sex, red/life, orange/healing, yellow/sun, green/nature, turquoise/art, indigo/serenity, and violet/spirit. The rainbow is one thing and many things, a unified community of multiple concerns for spirituality, love, culture, and environment.

I appreciate the revolutionary impulse behind the original flag, with its representations of things LGBTQ people should protect and hold sacred. But I also see that the meanings behind the rainbow flag are rarely known. I see how the flag’s use is glaringly anti-revolutionary when banks, shopping centers, and police stations wield it. And the community that produced the original flag, despite its utopian ideals, would often throw those of us who don't find ourselves neatly explained by this flag under the bus for not being white enough, cis enough, masculine enough, rich enough, or otherwise “normal” enough. For some of us, the rainbow flag represents exclusion from the homonormative, “respectable” queer society.

None of this is to say that flags are bad, or that we shouldn't use them to express our identities, our values, or our allyship. But there are limitations to what the flags might show us, of what we see in them, of how flags direct us to see.

Optics for Transformation

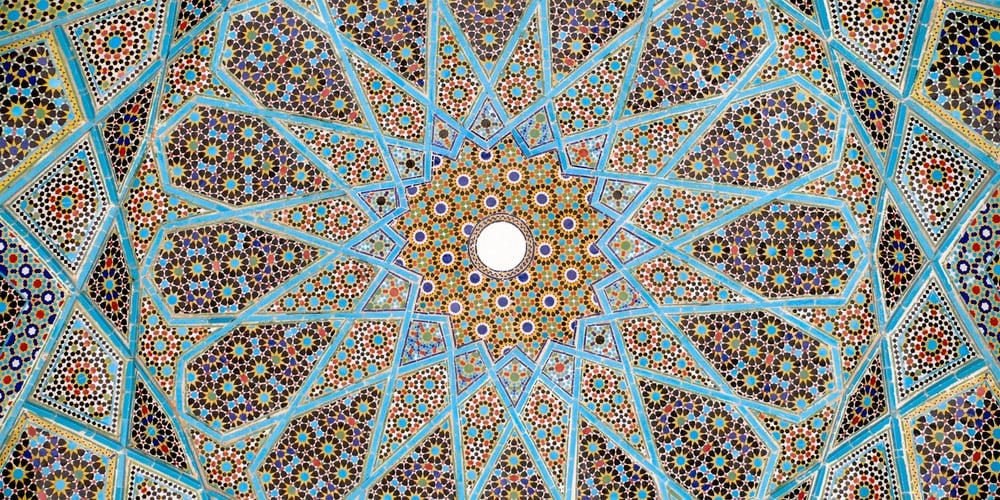

I want to offer an additional symbol of Pride optics to our repertoire, one that is already part of it, but obscured and forgotten in our current age: the teleidoscope. The teleidoscope is a cousin of the more familiar kaleidoscope. But they differ in a critical way. A kaleidoscope is filled with colored shapes or beads, and through the mechanisms of an eye in isolation, of chambers in rotation, of images in reflection, it creates a private world comprising a multiplicity of shapes. This world, in the traditional kaleidoscope, is interior. It belongs to a single onlooker. If two people stand side-by-side, for instance, looking in the same direction, each looking through their own kaleidoscope, the one person has no reference to what the other sees.

The same cannot be said of the variant teleidoscope.

A teleidoscope

A teleidoscope

Instead of beads or colored glass, the end of the teleidoscope includes a sort of clear marble, and the patterns we see when looking through it are the reflections, distortions, fragmentations, and repetitions of exterior objects. If two people are standing next to each other, looking in the same direction through their teleidoscopes—perhaps staring at the same vase—they are seeing the same object, albeit not from the same perspective.

The world that each perceives is unique, and yet similar, made of the same stuff. The relationship between unique eye, angle of the marble, and refracted light creates something specific out of something shared. If we think of sight as a back and forth and imagine ourselves on the receiving end of the objects we perceive, then each onlooker is also looked at, refracted, contorted, and so revealed as possessing and being possessed by fluctuations of shapes, shadows, and light. Here, there is no illusion of separation between an interior event perceived and the exterior world of the seer. Everything seen and seeing is implicated in the emergence of beauty.

The teleidoscope was invented, or at least patented, by John Burnside in the 1960s. Burnside was also a gay rights activist and long-time partner of Harry Hay, communist, indigenous rights activist, gay liberationist, and founder of both the Mattachine Society and the Radical Faeries (a gay/third gender spirituality). At the core of Hay’s advocacy is the idea of subject-subject consciousness. That is, he wrote about the ways queer communities disrupt subject-object relationships.

A teleidoscopic vision—queer vision.

The teleidoscope reveals in every “object” a multiplicity and the dynamism of malleability that we usually only attribute to subjects rather than objects: the ability to change, to grow, to reveal something new, and to enact difference in the world. In seeing the other’s dynamism, I am reminded that I, too, am not one alone but many in my relationships. We are communities, shapes, and bodies in relational rotations.

Queer vision is seeing the dynamism, creativity, and agency of those we love. Queer vision is seeing that the objectification of others results in our own petrification. The heart of queerness is seeing the movement in another, and letting another draw out our movement, our own dynamism, our own growth and generativity. When we refuse to be seen in our own multiplicities, when we do not let relationships live and grow, we become objects.

How might we practice queer, teleidoscopic vision in our theologies? Process? Pluralisms? Non-dualism? Liberationism?

What do we see if we look at our communities, families, friends, allies, accomplices, and mentors through a teleidoscope to see a single world in all its refracted multiplicity? We see Sylvia Rivera who saw herself as trans woman, drag queen, gay man, and gay woman. We see Leslie Feinberg who was he, she, and zi, contextually determined. We see rigid boundaries of sex, gender, and sexuality blurring, melting, shifting. We see communities building borders and communities crossing borders--even communities abolishing borders. We see a living flame and a murmuring depth of primordial water. And we see that to take pride in each of our identities—who each of us is—is to take pride in a series of patterns formed not in isolation, but in deep, ever-changing, relationship.

Happy Pride 2020.

Your Comments :