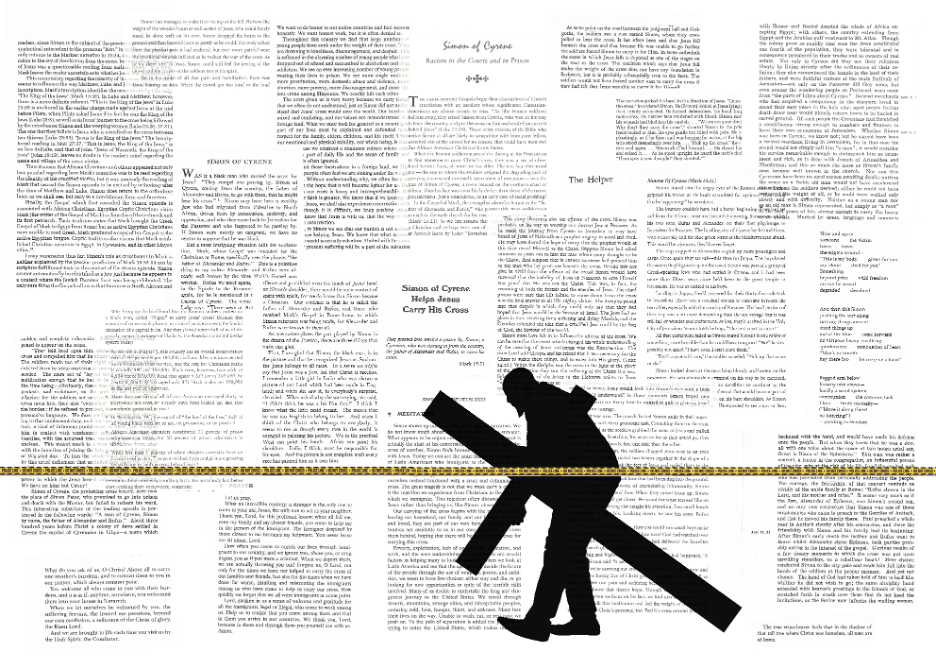

The Stations of the Cross has its origins in the early Christian practice of visiting the sites of Jesus’ passion in Jerusalem. Over the centuries, it has since developed into a kind of mini- or local pilgrimage in which the faithful process through the fourteen stations, often represented by plaques or artwork within a church building. In a time of pandemic, we invite you to join us on an imaginative pilgrimage through the following artists' images, poems, and reflections.

- Jesus is condemned to death.

By Dustin Wilsor

- Jesus carries his cross.

By Dee Grover

- Jesus Falls for the first time.

By Andrea Roselle

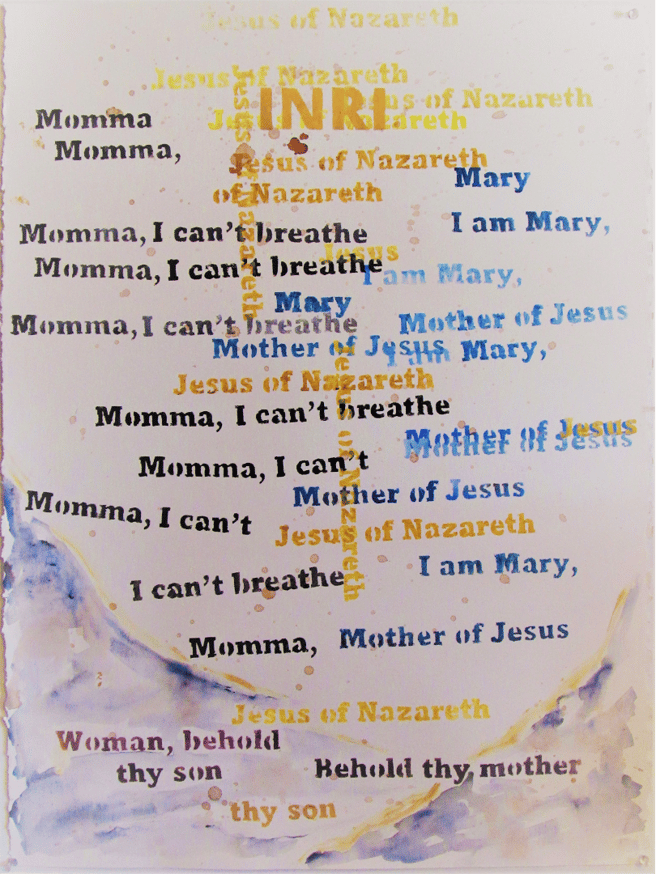

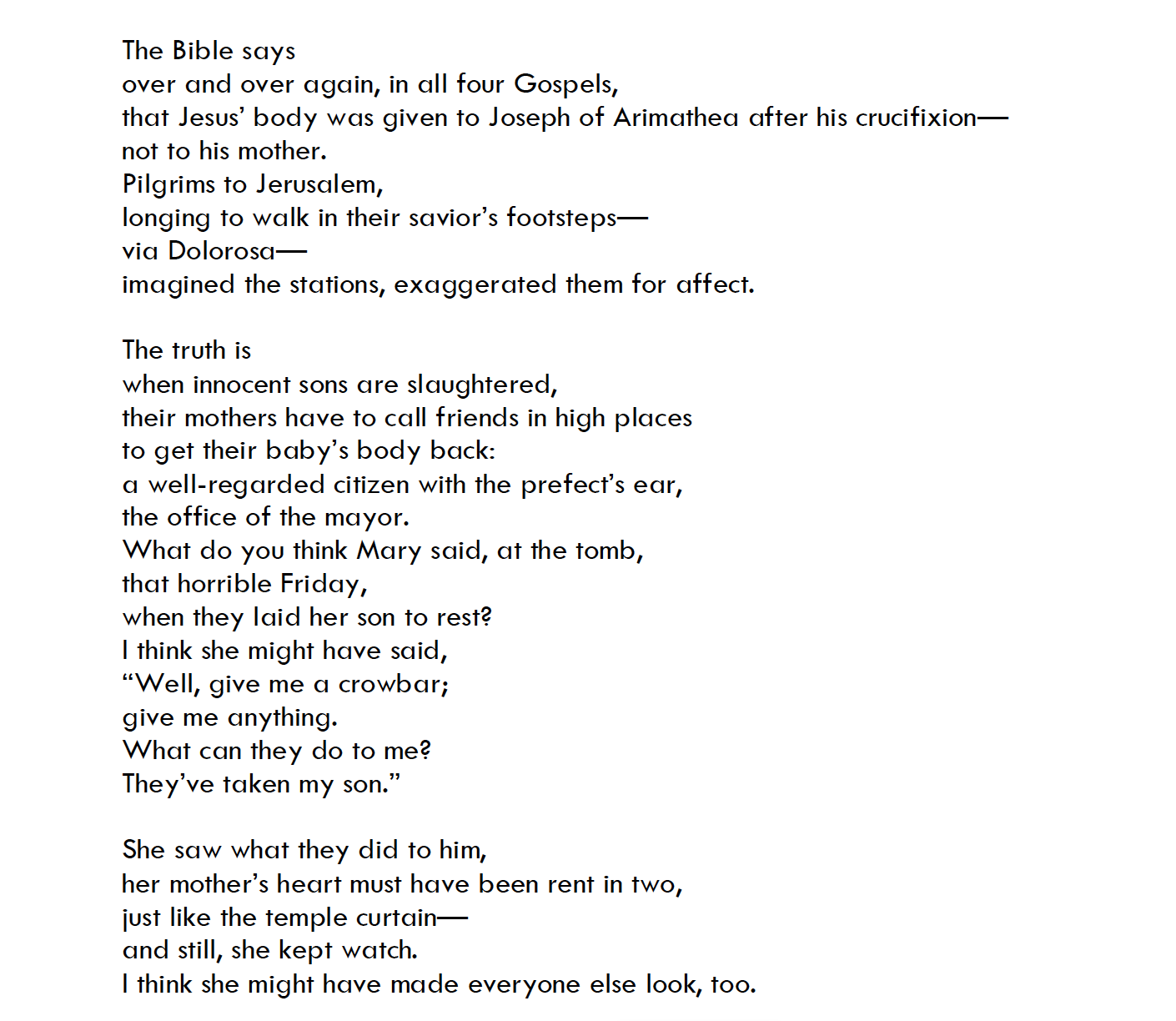

- Jesus meets his mother Mary.

By Elizabeth Jacobson

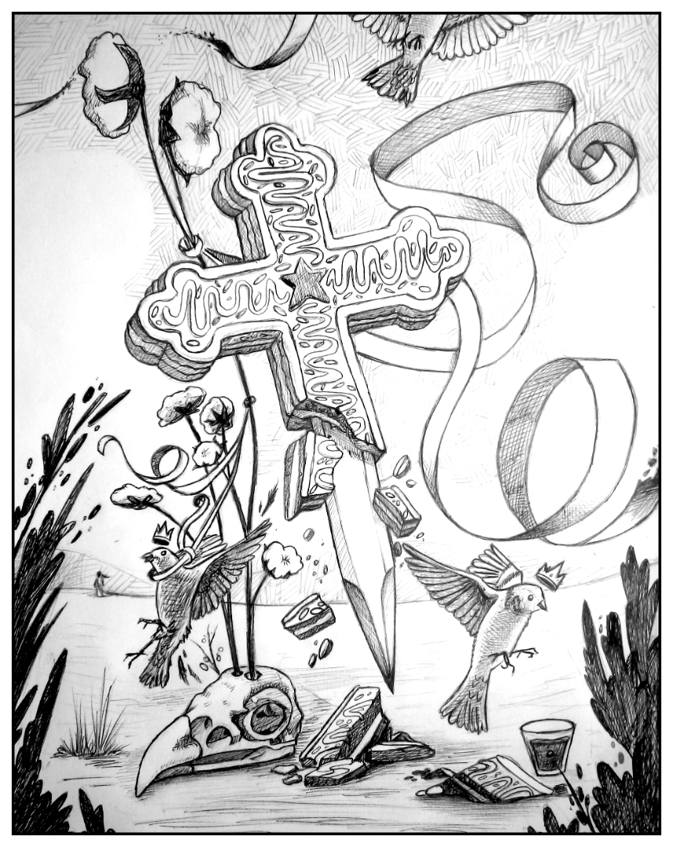

- Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry the cross.

By Justin Sabia-Tanis

- Veronica wipes the face of Jesus.

By Alaina Hoffman

- Jesus falls the second time

By Jennifer Awes Freeman

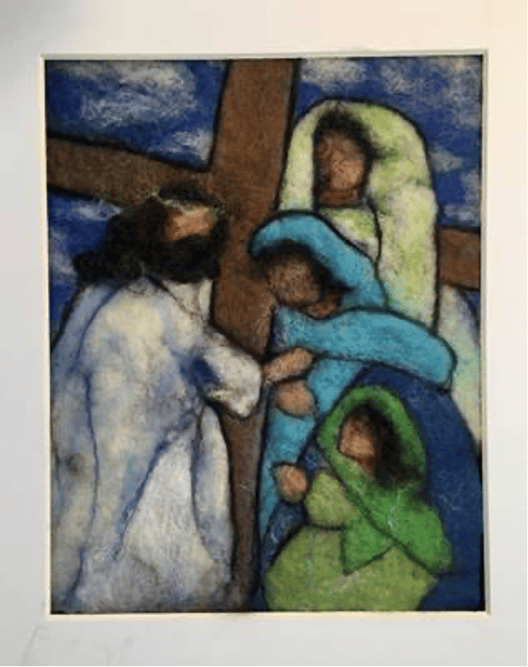

- Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem

By Melissa Miller

Jesus spent much of his earthly life comforting, healing, uplifting, protecting, and empowering women. Here, women lean in to offer their consoling embrace to him. They represent the women of the world weeping for justice and mercy, while teaching us the beauty of compassion that flows through our wordless tears. Yet even in his final hour, Jesus stops to comfort the sad; a simple act of grace to calm them as he foretells the destruction to come.

“Do not weep for me, but weep for yourselves and for your children.”

- Jesus falls for the third time

By Elizabeth O’Sullivan

- Jesus is stripped of his clothes.

By Max Yeshaye Brumberg-Kraus

Note: The original video is not included here due to nudity and sexual content.

In lieu of cutting out scenes or censoring images in the video, the artist has agreed to replace their submission with the following passage from the 19th Ecumenical Council held between 1545-1563: “Moreover, in the invocation of saints, the veneration of relics, and the sacred use of images, every superstition shall be removed, all filthy lucre be abolished; finally, all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust […] In fine, let so great care and diligence be used herein by bishops, as that there be nothing seen that is disorderly, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God.”

Baring the Cross Artist Statement

Max Yeshaye Brumberg-Kraus

In Station 10, Jesus is stripped of his garments and the Roman soldiers divvy up his clothes. The Vatican links this station to the Edenic tragedy: “the expulsion from Paradise: God’s splendour has fallen away from man, who now stands naked and exposed, unclad and ashamed.”[1]

In Eden, the serpent tells Eve: “your eyes shall be open, and ye shall be as gods.”[2] Thus she eats the fruit. Is the serpent simply a liar, or is nakedness a revelation? Human’s first knowledge is knowledge of the nude self: “the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked.” Look. Desire. Know: apotheosis. Sight becomes self-sight and sight of the other. Please me, and I will please you: see my nakedness, and we will be as gods.

If the gift of Jesus’s body to the world is also his revelation, how might the naked body in Paradise similarly be gift and revelation. What occurred between the opening of their eyes and the eventual shame? Did Eve and Adam experience a frightening, mutual self-objectification, a giving of oneself to the other, a move to queer subject-subject consciousness, a mutual relinquishing of self out of love for the other and in so doing approach divinity? But they ultimately withdraw from divinity. God walks in Eden, and the humans “hid themselves […] amongst the trees of the garden.” They do not give unto God, but hoard their flesh: “I was afraid […] I was naked; and I hid myself.”[3] Unable to relinquish themselves to one another, let alone to God, the humans revert to a hierarchical relationship, a heterosexuality ordained by a God who has seen his humans fail to be gods, failed to give as gods, generously, through their skin. God decrees Adam the doer, Eve the done, Adam the actor, Eve acted upon, subject and object. And if God was any good, perhaps God wept.

Christ, divine incarnation, arrives to undo this paradigm, the god/man enacting agency through his own objectification, giving unto others as they should give of themselves. But when the Romans bare Jesus, they still bear clothes upon their backs. They devour him not as living nourishment, but in a perverse Eucharist of Jesus’s possessions and Jesus as possession. Is this the origin of Christianity

With an added layer of interpretation through “The Twa Corbies,”[4] a Scots folk ballad in which two birds discuss an abandoned corpse they are about to eat and incorporate into their nest, the Romans are both compared to and contrasted with carrion eaters. For while magpies and crows are emblematic of natural life contingent on death, Rome and Christendom are emblematic of supernatural life contingent on killing.

Contrasting Christian colonization, dehumanization, and capital with the genderbent, stripper Christ, Baring the Cross asks how do we see our bodies and give our bodies, how are our bodies seen and taken, how might queer and trans people—the sexual and gender marginalized--know God’s body, and ultimately, what is most shameful: a body stripped or the stripping of the body?

[1] “Tenth Station,” https://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/2005/via_crucis/en/station_10.html

[2] Gen 3:4, 3:7 KJV

[3] Gen 3:8, 3:10

[4] “Child Ballad 26: The Three Ravens/Twa Corbies,” in Bertrand Harris Bronsin and Francis James Child, The traditional tunes of the Child ballads: with their texts, according to the extant records of Great Britain and America (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1959).

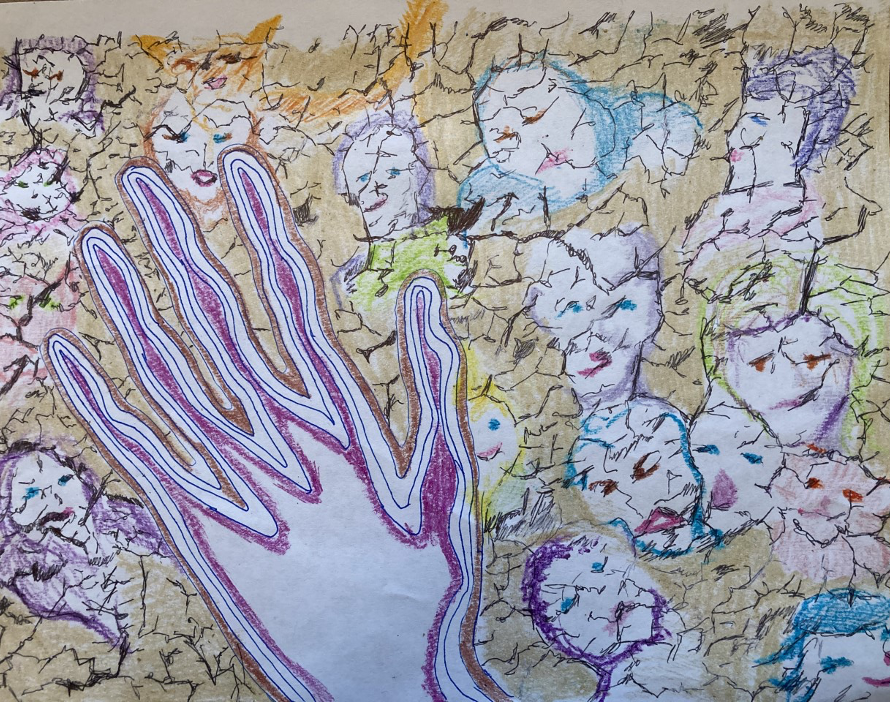

- Jesus is nailed to the cross.

By Ben Steckelberg

.

.

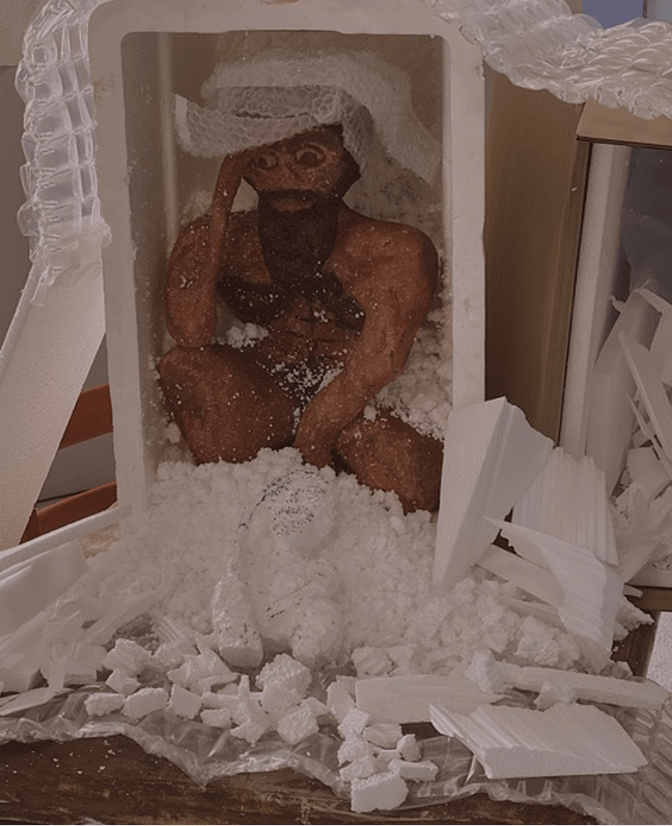

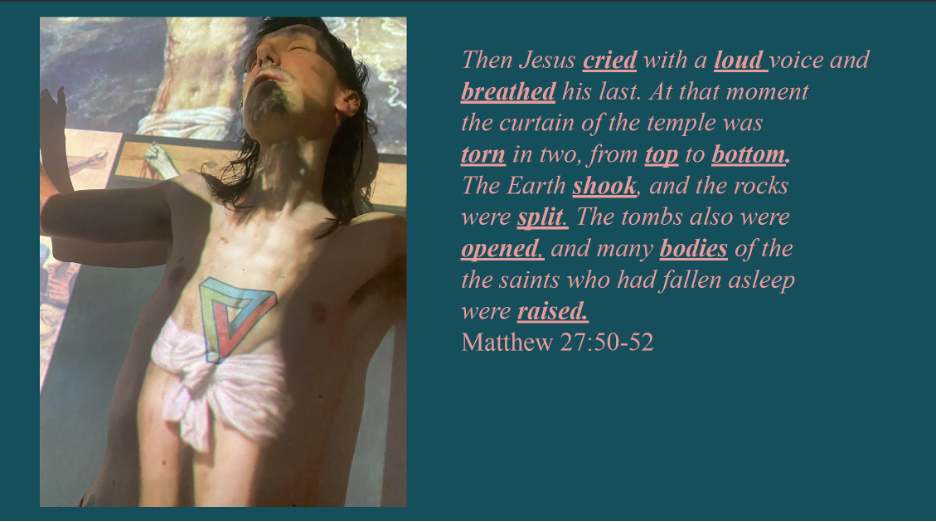

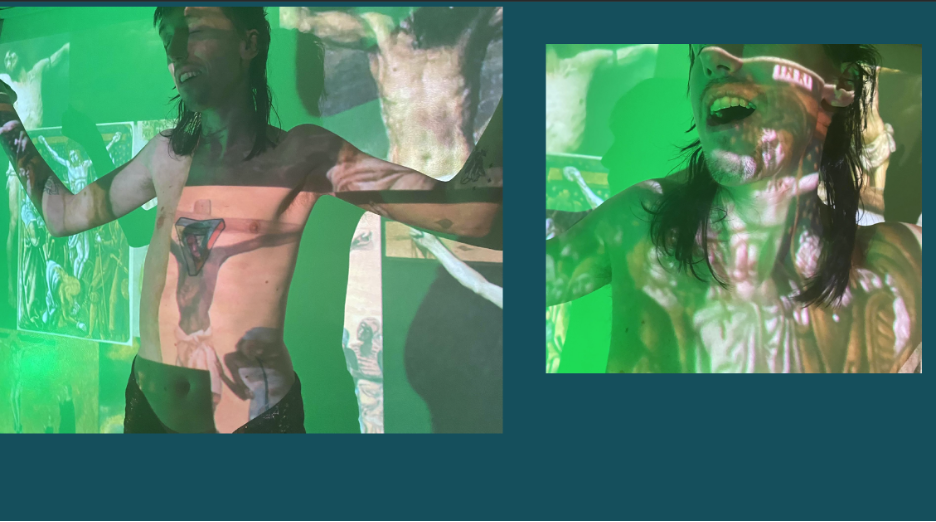

- Jesus dies on the cross.

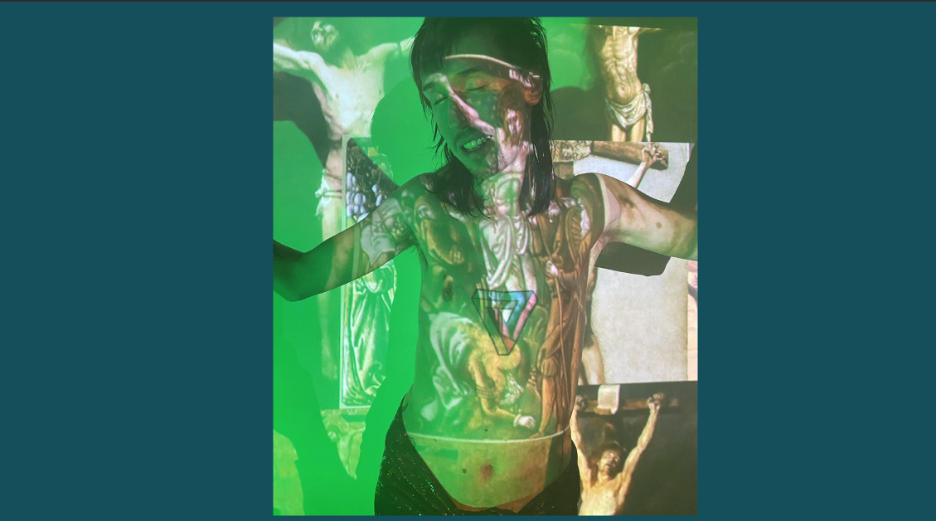

By Jäc Miller

Released

the 12th station of the cross

Artist Statement by Jäc Miller

This project began after a conversation I had with someone, who got me thinking about death as an orgasm. Especially Jesus’s death, who at the moment of passing shook the earth, split rocks, and tore open the curtain inside the temple. This language in Matthew describing Jesus’s death such as cried, breathed, loud, shook, opened, etc. could easily being describing an orgasm. Like an orgasm, Jesus’s death comes after a buildup of tension inside his body finally arriving at its moment of release. “Released” was a physical exploration that asks us to visualize the twelfth station as synonymous with orgasmic release.

The body in these images is not meant to be Jesus. Rather, I wanted to visualize the moment of Jesus’s death in our bodies, a queer body feeling pleasure. Hence the literal projection of many Jesuses onto the model. With help from myself, the model explored feelings of pleasure, tension, and release, while keeping in mind the shape and quality of the image or images being projected. The images being projected were meant to remind viewers of the countless times this image has come before them. I wanted to ground their gaze in the familiar, while showing them something unfamiliar and intimate.

The use of light allowed us to see different feelings of this release. The red offers a more intense feeling, reminiscent of being inside a dungeon or a BDSM club. Green keeps us cooler and in a calmer state. The question about color became “what kind of feeling do we often see in Jesus’s final release?” and “what colors represent the feeling that the Son of God felt when he took his last breath?” The lighting was the first element we had for this project, as I knew I wanted to implement shadows. The shadows became a way to explore the visual of one's spirit leaving their body at the time of death or the time of an orgasm. The shadows helped decide the angle of each shot.

This image series began by asking “how do shadows and light help us to discover something new about the twelfth station?” and “how can we use our own bodies to make those discoveries.” There are more images if anyone is interested.

- Jesus is taken down from the Cross.

By Meg Mercury

Station Thirteen, at Fourteen

- Jesus is placed in the tomb.

By Sam Carwyn

Image courtesy of Jonny Gios via Unsplash.

Image courtesy of Jonny Gios via Unsplash.

May the loving power of God,

strengthen you in hope,

enrich you with love,

and fill you with joy.

Your Comments :